An American Aristocrat

An American Aristocrat

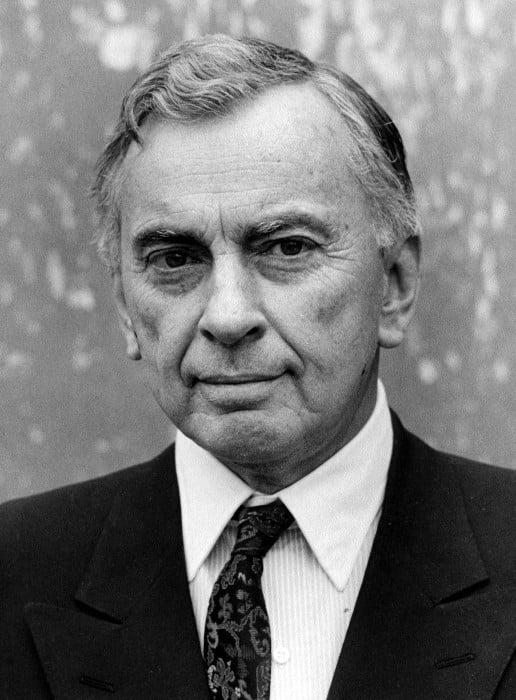

Flamboyant, educated, haughty, charming, outspoken, political, dignified, observant, broad-minded, funny: Gore Vidal was a man born to ruffle feathers and challenge convention. He managed to do just that for over five decades, placing him in the same league as American authors like Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson, Philip Roth, and Kurt Vonnegut.

Some of his work, like his essays on literary criticism, are impenetrably dense even to people who are acquainted with their subject matter. The best novels by Gore Vidal, by contrast, are fantastically easy to read simply as entertaining stories. You don’t need to go digging for symbolism in them, even if he doesn’t bother to dumb down his themes or his acerbic wit.

Sometimes Controversial

Vidal is especially known for telling a whole, complex joke in only half-a-dozen words. These are sometimes directed at people he doesn’t like: over the years, his views on politics and sexual liberation have made him quite a few enemies.

You don’t have to love Gore Vidal, you don’t even have to agree with him. You can’t ignore him, though: both as a literary giant and an American political commentator, he has few equals. Here are ten of my favorite Gore Vidal books, ranked without regard for their date of publication:

Best Gore Vidal Books

| Photo | Title | Rating | Length | Buy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lincoln | 9.92/10 | 937 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

Julian | 9.86/10 | 509 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

Creation | 9.82/10 | 593 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

Burr | 9.72/10 | 635 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

The City and the Pillar | 9.58/10 | 229 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

Lincoln

Neither Hero-Worship Nor Villain-Shaming

Neither Hero-Worship Nor Villain-Shaming

One quality you’ll soon notice in all of Gore Vidal’s best books is that none of his characters are either entirely good or completely bad. This extends to historical figures, too. He treats the Roman emperor Tiberius with kindness, for instance, while other historians almost universally despise him. Contrariwise, he depicts the 16th American president not as the almost-mythological figure he’s often made out to be, but as a man with his own doubts, fears, and failings.

Truly, this humanizing approach yields a far more interesting character than one who always knows what to do, never compromises, and rarely has a bad day. If nothing else, this book demonstrates that the Thirteenth Amendment, finally passed only in 1865, was anything but a foregone conclusion.

Part of a Larger Whole

Lincoln is the second book in Narratives of Empire, the best Gore Vidal series to read if you hope to figure out how the United States came to be what it is today. According to Vidal, at least, this means on the verge of moral, intellectual, and political bankruptcy. He also believes that this is in large part due to a history of militarism, in which the legacy of the Civil War plays a notable part.

This is certainly one of the best Gore Vidal novels and, though mostly fictional, remains true to meticulously researched historical facts. When it comes to the true natures and intentions of the many well-known figures portrayed in Lincoln, however, you’re welcome to either accept Vidal’s suppositions or make your own.

Julian

An Often-Misunderstood Protagonist

An Often-Misunderstood Protagonist

Like Tiberius (and even Nero, for that matter), most of what we know about the Roman emperor Julian comes from historical sources. Many of these were lost or destroyed, few were ever written from the perspective of ordinary citizens, and quite a few were disparaged, overemphasized, or even altered by history’s victors. It’s for this reason that most people know him as Julian the Apostate, the enemy of Christianity and therefore kind of a scumbag.

Seen objectively, though, Julian was a notable intellectual, a levelheaded ruler, a competent military commander, and even a kind of martyr; a victim of divisive politics and religious extremism. This is the side of Julian portrayed by Vidal.

Timeless Lessons

Although first published way back in 1964, Julian remains one of the best-selling Gore Vidal books. As a novel, it certainly beats any dry recitation of the bare facts.

Some people will certainly find its core theme, or at least the identity of the antagonists, difficult to swallow. The Christians, or Galileans as they’re called, are bigots, enemies of knowledge, hungry for political power, and unwilling to allow other points of view to exist. Even if this offends you, you’ll still enjoy Vidal’s superb prose and insightful characterization. You will certainly be able to find many parallels to events in this book in the modern world, and possibly closer to home than you’d like.

Creation

Dusty History, Brought to Life

Dusty History, Brought to Life

Most people’s knowledge of the era around the year 500 B.C., when Creation is set, is pretty much restricted to what they saw in the movie 300. In reality, this is the first period we have any reliable history of, and plenty of exciting stuff was going on.

Bronze was slowly being replaced by iron, Confucius was a civil servant in a mysterious, far-off land, the Buddha was still alive, theological notions of good and evil had barely been invented, Rome was only a minor Italian city, Persia (modern-day Iran) was the world’s superpower, and Athens was still trying to get used to the idea of democracy. Ambitiously, Creation covers many of these subjects and more, leading to one of the best books by Gore Vidal ever.

Starting at the Root

Spitama, our blind, wise narrator, provides a sweeping first-person account of the beginnings of modern politics, religion, and civilization itself. Much of this runs contrary to history both as taught in ancient Hellenic society (which offends Spitama mightily) as well as what most people think they know today.

Very little of Spitama’s own personality is injected into the tone of the narrative, though. He remains a mostly detached observer. The book as a whole could certainly have used a little more texture and animation throughout its 600 pages. For sheer scope, scholarly research, and readability, though, this may well be the best historical Gore Vidal novel.

Burr

A Complex Figure

A Complex Figure

Aaron Burr appears in the musical Hamilton, first as the main character’s friend and later as his rival and, in fact, the man who ends up killing him. Later on, he was even accused (and acquitted) of treason against the young republic due to his shenanigans on the western frontier. Historically and in this novel, though, Burr was far more than a stereotypical bad guy.

Stereotypical good guys, of course, don’t always do so well in the real world, least of all in politics. A superficial look at Aaron Burr’s character reveals many apparent contradictions. He, for instance, tried to abolish slavery as far back as 1785 though he himself owned slaves. He also believed that women were intellectually equal to men and should have the right to vote, but this didn’t stop him from being a notorious womanizer.

Sympathy for the Devil

As in many of the top Gore Vidal books based on historical events, the author did his own research and insisted on drawing his own conclusions. These are almost invariably irreverent, as is the biting wit that makes an appearance at every opportunity.

This is the first and arguably best book in the Gore Vidal series Narratives of Empire. If you believe in that old saying about those who do not understand history repeating it, this is a must-read.

The City and the Pillar

Gasp! How Dare He?

Gasp! How Dare He?

One of the many things people have held against Gore Vidal over the years was his bisexuality. This was a tectonically huge deal back in the 40s when this book was published. Vidal went right ahead anyway, not even bothering with a pseudonym.

Apart from examining prejudice and its consequences, and of course simply mentioning the idea that two men can love each other, this is really a romantic coming-of-age novel. Despite all the hoopla when it came out (so to speak!), it’s not a gay story, it’s just a story about people who happen to be gay.

A Substantial Early Work

Though Vidal didn’t shy from the inevitable controversy (he had major trouble finding work or promoting his books for years afterward), he also didn’t go out of his way to court it. The simple, unaffected way in which he treats his subject matter greatly increases this book’s enduring appeal.

Some readers will find the description of the post-WWII American gay scene interesting. Others will admire the quality of the writing. Despite being only his third novel and completed when he was only 21 years old, the prose of The City and the Pillar already shows signs of the author’s genius. This is by no means the brightest star on the Gore Vidal book list, but it’s pretty much a masterpiece in its own right.

Palimpsest

Looking Back

Looking Back

Several early The City and the Pillar book reviews claimed that it was Gore Vidal’s own experiences translated into a fictional format. This is not the case, as the author has always maintained.

Palimpsest, however, is the real deal. Before you reach for your dictionary, the word refers to a piece of parchment that’s been erased by scratching off the top layer. A ghost of the old writing still remains visible, though. To Vidal, this is a metaphor for the process of literary creation. Starting with his own observations, he scribbles down his thoughts, then refines them, until what’s left includes layers of echoes upon echoes.

Something of a Misanthrope

This author was the product of a prominent and somewhat turbulent household. Later, the trajectory of his career brought him into the orbit of many well-known figures, including writers, actors, and politicians you’ll easily recognize by name. Vidal’s descriptions of them in their private moments are often less than flattering.

Instead of a typical autobiography, namely a series of events, encounters, and conversations, Palimpsest is largely a work of subjective reflection. You wouldn’t be the first reader to feel a smidgen of envy at his extraordinary life: Vidal has always been one to march to his own drum. On the other hand, he often comes off as pompous and self-centered; however well-written, it seems to lacks authenticity and therefore is not Gore Vidal’s best book.

Empire

A Story of a World in Flux

A Story of a World in Flux

Chronologically, this is the fourth book in the Narratives of Empire series. It picks up shortly after the events depicted in 1876. Technological marvels never dreamt of before can suddenly be ordered through the mail, there are fortunes to be made by those willing to grasp them, and America is rapidly changing from a former colony to a force to be reckoned with.

Of course, as in 1876 and indeed most of American history, power does not attract only the virtuous. This needn’t mean running for elected office (as Vidal did twice, incidentally). The men behind the curtain – newspaper owners, editors, and writers – are more than willing to use the influence of the printing press to get what they want.

America at the Start of Modernity

These intensively researched novels provide an easy way to learn more about U.S. history. This fact partly explains why the Narratives of Empire series are consistently among the best-rated Gore Vidal books. They’re not just a record of who did and said what, though. Their greatest strength is that they provide entirely plausible guesses as to the motives and hopes of those who ended up shaping the America of today.

Unlike in Lincoln and Burr, the main protagonists are not those at the center of events. As somewhat detached yet involved observers (much like Vidal himself), their interactions with the rich and famous manage to paint interesting and insightful portraits of several notable figures.

1876

Warts and All

Warts and All

It may come as a surprise to many Americans, but divisive rhetoric, ad hominem attacks, and outright slander are nothing new in U.S. politics. Compared to the 1796 contest between so-called statesmen John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, for instance, the 2016 election was an elegant baby shower mostly remembered for the tea and crumpets served.

One hundred years after the first Independence day, whatever special brand of virtue the founding fathers possessed had long since evaporated. The ultra-rich bought and sold politicians as if they were racehorses, the spoils system (organized cronyism and nepotism) was an accepted fact of life, and many citizens were impoverished and desperate.

Slow But Not Bad

Though still one of the most popular Gore Vidal books, 1876 lacks some of the charm and wit of others in the Narratives of Empire series (seven in total). The plot is somewhat sluggish and bogged down in the minutiae of upper-class life in the late 19th century. Much of the story is developed through idle conversations where nothing much happens and little of true importance is said.

It’s still worth reading, though, especially in an election year. For one thing, despite its somewhat pessimistic tone, it does make the point that the American political system has never been perfect, but still manages to muddle along somehow.

Myra Breckinridge

Bound to Offend Someone

Bound to Offend Someone

As someone who was openly bisexual even back when the words “gay” and “lynch mob” were closely associated, this author naturally has a couple of firmly held opinions on what we call “gender politics” today. Being Gore Vidal, these opinions are also sometimes the last ones you’d expect.

Myra Breckinridge is probably the best Gore Vidal book on social issues aside from politics. Like The City and the Pillar, it attracted a torrent of criticism from religious and traditionally minded groups, quickly became a bestseller, and encouraged an entire generation to rethink their ideas about gender and sexuality.

Helter Skelter

Remarkably, this novel was supposedly written in only a month. The plot jumps all over the place, much like the protagonist’s gender identity. A lot of the writing is also pretty explicit, certainly by the standards of the late 1960s. If you have a major puritanical streak, or you’re addicted to viewing the world through a traditionally macho lens, or, in fact, you get the hiccups any time the norms of gender and sexuality accepted today are challenged, you’ll probably want to go with Julian instead.

Myra Breckinridge is above all a parody: of homosexuality, homophobia, Hollywood, men, women, and America itself. Read it as satire. This deliberately outrageous book is meant to entertain, not to make a specific statement. The same is true of the sequel, Myron, published several years later.

Washington, D.C.

Like Peanuts, You Can’t Devour Just One

Like Peanuts, You Can’t Devour Just One

Washington, D.C.’s timeframe partially overlaps with that of Gore Vidal’s last book in the Narratives of Empire series, The Golden Age. It says a great deal that these historical novels dominate my 10-best list (the only ones excluded are that one and Hollywood), even if that means leaving out classic Vidal novels like Kalki and Duluth.

For one thing, using well-known (though frequently misunderstood) historical figures as vehicles for this author’s insight and biting wit makes these books far more approachable than they’d otherwise be. For another, the series as a whole is simply an incredible body of work, almost worthy of being mentioned in the same breath as The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

A World Apart from the Common Man

Washington, D.C. happens to have been written first. Though obviously well-researched, it’s also the most fictional of all the Narratives of Empire books. It’s also atypical in that it does not revolve around the most famous people of its era, namely the administrations of Franklin Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower.

Like all the best Gore Vidal books that reference politics, this narrative strays far from the sanitized, idealistic outlook TV commentators like to espouse. According to Vidal, politicians (called “devoted enemies of the people” by one character) are not as much interested in using their power for good as power itself. This happens to be the world Vidal grew up in. You may disagree with his viewpoint, but you cannot simply dismiss it.

Final Thoughts

Usually, it’s a bad idea to read Gore Vidal’s books in order to decide whether or not you approve of him. He was never one to exert or compromise himself just to make friends.

At the same time, though, he never talks down to the reader or tries to be clever for cleverness’ sake. Characters are always a complex mixture of good and evil. He’s often critical, but rarely callous. In short, he’s a demanding writer and one that’s sure to push your intellectual boundaries, and therefore well worth reading.

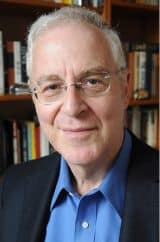

Michael Englert

Michael is a graduate of cultural studies and history. He enjoys a good bottle of wine and (surprise, surprise) reading. As a small-town librarian, he is currently relishing the silence and peaceful atmosphere that is prevailing.