Ahead of Her Time

Ahead of Her Time

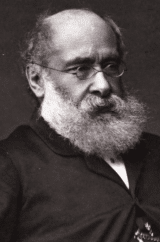

In case you didn’t know, George Eliot was a woman; in fact, her real name was Mary Ann Evans. This would ordinarily not be very significant, but Victorian England was a peculiar place.

Married women were only allowed to own property from 1882 onwards, eight years after George Eliot’s last book was published. Upper-class girls spent plenty of time learning crafts like music and embroidery, though for the most part their formal education was restricted to what they would need to manage a household and servants. Women essentially lost all rights the moment they got married, yet marriage was still seen as the best outcome they could hope for in life.

Best George Eliot Books

| Photo | Title | Rating | Length | Buy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Middlemarch | 9.92/10 | 533 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

Daniel Deronda | 9.82/10 | 372 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

The Mill on the Floss | 9.74/10 | 618 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

Adam Bede | 9.66/10 | 453 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

Silas Marner | 6.60/10 | 218 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

A Polite Iconoclast

Naturally, an intelligent woman growing up in this environment could be expected to develop a few controversial views. Eliot didn’t exactly flaunt her multiple sexual relationships, her heterodox views on religion, or her desire for greater equality between genders and different social classes. She didn’t bother to hide them, though, either in her private life or her work.

Despite this, her popularity as a novelist never suffered even after she revealed her identity. (Supposedly, even Queen Victoria was a fan.) Her vivid, realistic, and moving descriptions and characterizations are still praised today, though her opinions are no longer even remotely radical. Here are the eight most-read George Eliot books in order of how much I personally enjoyed them:

Middlemarch

Few Flights of Fancy

Few Flights of Fancy

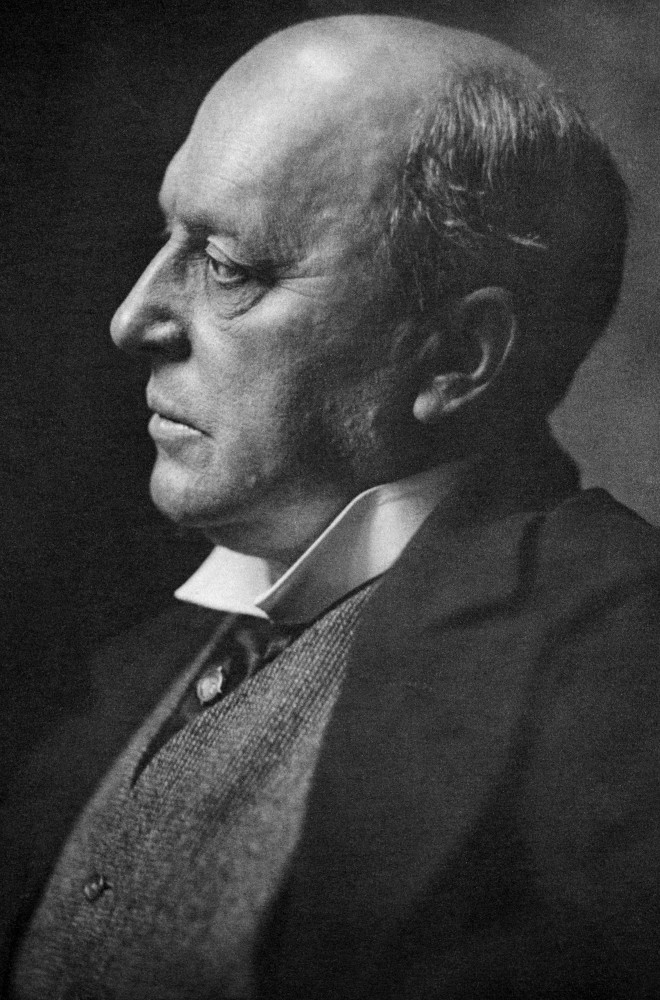

Eliot, along with her near-contemporaries Émile Zola, Jane Austen, and Henry James, was a fan of the realist movement both in visual art and literature. This means that she spends considerable time describing apparently mundane details, showing them just as they are without injecting too many of her own impressions. Her plots are also similarly grounded in reality – implausible, frivolous plots are something she specifically criticized about the writing of female English novelists who were popular in her time.

In addition, her characters are always believable. In Middlemarch, many of these were probably modeled on people she knew early in life. As her father was a valued foreman on a wealthy family’s country estate, she came into contact with people from many walks of life. This interplay between rich and poor is a common feature in the best novels by George Eliot.

Green and Pleasant Land

Middlemarch is set in the British Midlands, the rural heartland of England. Eliot does a magnificent job of sketching the scenery, with which she was very familiar, in great depth. Those who populate it are given similarly generous treatment: though they are to some extent defined by social roles that are now outdated, it doesn’t take much to recognize parts of your acquaintances in many of them.

This book has been extensively praised as the best George Eliot novel including by other famous authors, which has to count for something. Though some of the themes are fairly challenging, it’s still a pretty lighthearted and entertaining read despite the old-fashioned language. It’s very, very long, though well-structured. The complex, interlocking subplots can be difficult to follow if you can only spend an hour a week reading for pleasure. Perhaps it’s time for a digital detox or a week without TV?

Daniel Deronda

Enlightened Satire

Enlightened Satire

Eliot finished this book as her partner, the controversial philosopher George Lewes, was nearing the end of his life. They openly lived together as a couple despite not being married. This was, of course, scandalous in a society where finding something to be Positively Outraged about, however normal and harmless, was a national pastime.

Each was also deeply involved in the other’s work. Their mutual rejection of received wisdom and dubious social standards provide much of the meat in Daniel Deronda. Parts of the book are even set in Germany, where Eliot and Lewes traveled together to research the lives and work of German poets. The way the author picks at the threads of Victorian society, but even more so the way Jewish characters are portrayed, lead to plenty of letters to that time’s equivalent of The Daily Mail (a conservative, lowest-common-denominator British newspaper), which naturally only contributed to Daniel Deronda becoming one of the best-selling George Eliot books.

Two Books in One

Daniel Deronda contains two distinct plots that are only barely connected. According to some of the harsher George Eliot book reviews, this novel should have been split in two. It may in fact have been better off that way: though the adventures of the female protagonist are always entertaining, much of the action regarding London’s Jewish community seems forced and contrived.

This failing should be seen against the book’s historical backdrop. Zionism was only getting off the ground, while public anti-semitism was common in Britain and most of Europe. It could be that Eliot deliberately set out to make a pro-Jewish statement rather than just following her muse. This ends up being only a minor drawback, though: as long as you can tolerate this author’s somewhat wordy prose, you’ll soon come to love her fully fleshed-out characters despite their conspicuous and very human flaws.

The Mill on the Floss

The Pull of Events

The Pull of Events

While Daniel Deronda is set in the latter half of the 19th century and primarily in urban environments, The Mill on the Floss returns us to the English countryside of a few decades earlier. The natural and period scenery, as in all the best books by George Eliot, is charmingly described. All is not as pastoral as it seems on the surface, though. Set during the Industrial Revolution sometime after the Napoleonic Wars, society and economic life are changing in subtle yet profound ways, leading to tensions beneath the surface.

Eliot, as usual, portrays these through the eyes of a complex web of well-written characters. Each is very much a whole person, with clearly discernible motives, values, and fears. They struggle against the circumstances an uncaring world thrusts them into, doing the best their capable of but not necessarily succeeding.

People Before Plot

The most important of these characters may as well be a fictionalized version of a young George Eliot herself. Sensitive, intelligent, stubborn, and rebellious, she’s almost destined to clash with her family even though she cares for them deeply. In a sense, she is a prisoner and victim of her own personality, as are several other characters in this book. However, she’s far from stagnant: her carefully plotted and chronicled development from adolescence to young adulthood easily rivals those of Hermann Hesse, and is arguably the best found in all of George Eliot’s novels.

While the protagonist is immortally unforgettable, her situation and the expectations laid on her by society (like having to marry one of only a few possible husbands, and as soon as possible at that) will not be familiar to modern readers. Nor are they made explicit in the text, as everyone in Eliot’s time would have known about and mostly accepted these conventions. Read the introduction to the edition I recommend above before starting, or it may take you 100 pages or more to figure these out.

Adam Bede

Strong Right out of the Gate

Strong Right out of the Gate

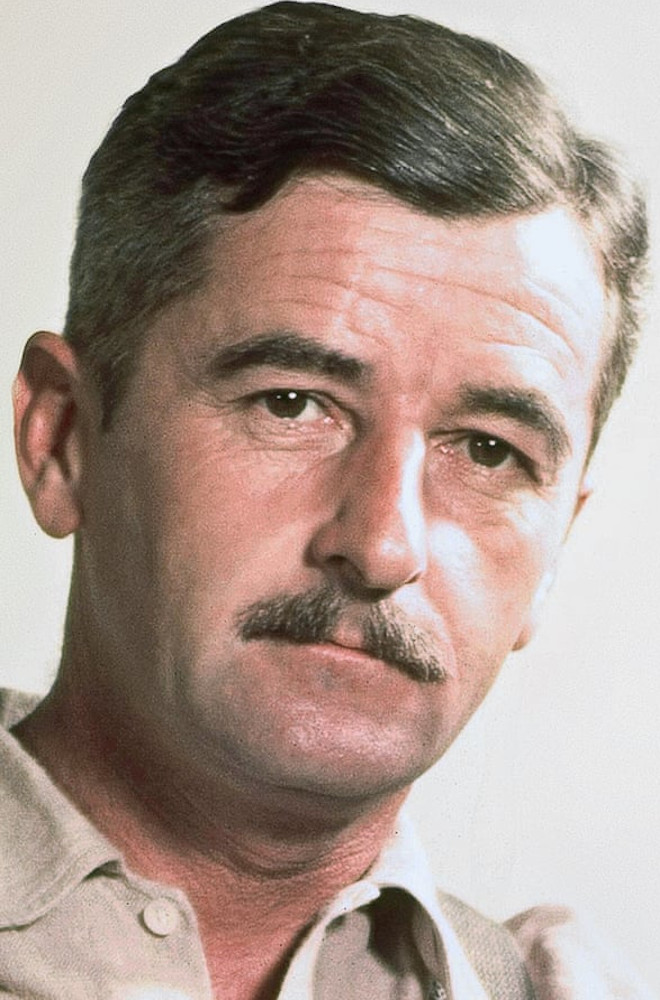

Though this was Eliot’s very first novel, she already had several years of experience with translation work (she was fluent in at least English, Greek, German, and Hebrew), newspaper editing, essay writing, and even a few short stories under her belt. It’s always interesting to see how an author’s first work balances experience with raw talent. Adam Bede surprises in this respect as one of the best George Eliot books, perhaps indicating that her kind of genius can’t be taught.

This also happens to be one of her darker books. Like in Middlemarch and in fact all of the top George Eliot books, there is plenty of wit and even outright jokes to be found. (The humor is definitely a little dated, though – comedy didn’t always revolve around sex and slipping on banana peels.) Though this author was never one to manipulate events in her books just to produce a happy ending, Adam Bede revolves around a love triangle with particularly tragic consequences.

One of Eliot’s Great Characters

The titular protagonist reminds me a little of Daniel Deronda in that book: an honorable, capable man who tries his best in every situation. You’ll remember the character of Hetty Sorrel far more vividly, though. Though she’s not entirely sympathetic and shares many of the “womanly” weaknesses Victorian literature is so choked with, the reader can’t help but root for her.

This book isn’t just about her, though, and Eliot’s penetrating psychological insight manages to populate the fictional community of Hayslope with a whole range of believable, balanced characters. As anyone who’s lived in a small town will know, city folk have nothing on their rural cousins when it comes to intrigue and pettiness. Yet Eliot also allows the finer human emotions – compassion, acceptance, and understanding – to shine through in this absolute masterpiece.

Silas Marner

Multiple Layers

Multiple Layers

If we’re being honest, many of George Eliot’s best books aren’t actually that complex or original when it comes to the basic plot. Yet it’s almost impossible to make a satisfying or even coherent movie out of any of them (not that this hasn’t been tried several times). The major hurdle seems to be that her books aren’t just sequences of events. Characters learn and grow, come to understand themselves and one another, and express their motivations through natural conversation rather than just blurting out “I wish…” or “I shall…”. Things only actually happen once each character can’t act any differently than they end up doing.

This generally leads to pretty long books (and unintentionally surrealistic screenplays). Silas Marner isn’t an example of this, though, weighing in at only a little over 100 pages. This probably makes it the best George Eliot book for total beginners, as you can get used to her style of writing without having to commit an entire month and perhaps a notebook to the project.

Little Treasure

At the same time, it also will not disappoint those who’ve already come to love Eliot’s work. Silas Marner features the same kinds of complex characters, minute yet interesting descriptions, and sincere yet un-preachy moralizing the best-rated George Eliot books share. Like most realist writers, her novels often have a deterministic streak: things simply happen to the characters without them deserving or being able to avoid them. If they’re worthy, their strength and courage are shown not in heroic opposition to the inevitable, but in dignified acceptance.

As usual, Eliot shines in portraying life in a different era. In this book, her views on politics, religion, and social justice don’t quite take center stage as they do in some of her other works. They’re never far from the surface, though, and are alluded to through their effects on the characters, not from some high-handed and abstract philosophical perspective.

Romola

A View on the Past, from the Past

A View on the Past, from the Past

Most of the George Eliot book list is set in times, places, and milieus that would have been completely familiar to the author. Romola is the exception, taking place in 15th-century Italy, a time and place that would have been as foreign to Eliot as her world is to us. People pretty much remain the same anywhere, though, and human nature was this writer’s true specialty.

As with her native England depicted in most popular George Eliot books, the author brilliantly manages to set the scene using detailed, down-to-earth descriptions of everyday activities. In many ways, in fact, Florence around the year 1492 resembles the Britain of Eliot’s day: established, intolerant religion is under threat of losing not only some of its flock but also its influence on government, the morals and values of the past no longer seem quite so ironclad, and the political establishment built up over the previous years is uncertain of surviving the coming week.

Every Hair in Place

Plenty of effort went into making the backdrop of Romola as true to life as possible. In addition to reading extensively, Eliot visited Florence several times while researching and planning the novel. Her descriptions of Florentine architecture are certainly more accurate and important on a symbolic level than those Dan Brown is famous for. Political events are also portrayed faithfully: Niccolò Machiavelli himself actually turns up now and again to explain to the characters and reader what exactly is going on with the Medicis and such.

This verisimilitude, from the details of political intrigue in Tuscany sown to what the characters’ clothes look like, still isn’t the lynchpin of this book. Aside from being incredibly (though sometimes cumbersomely) well-written, this is really a bildungsroman showing how the female protagonist develops from a naive girl to a worldly, cultured, and compassionate woman.

Felix Holt: The Radical

Somewhat on the Nose

Somewhat on the Nose

Personally, I like my propaganda delivered with a little subtlety. This is one of the things Eliot generally does very well, gently weaving her political opinions into a complex narrative instead of trying to storm the barricades of the reader’s mind. If we were to list George Eliot’s books ranked in terms of this kind of integrity, Daniel Deronda and Felix Holt would occupy the two bottom slots.

Of course, this by itself doesn’t make it a bad book. One of an author’s obligations, after all, is to shine a spotlight on issues that need to be addressed. There is a time and a place, of course, and Britain in 1866 was arguably it. Certainly, as Stacey Abrams points out, one of the main issues – the right to vote – hasn’t been completely settled even in modern-day America. The situation is far less dire than in Victorian England, though, and the author clearly choosing sides in the debate sometimes seems to detract from this George Eliot book’s best qualities.

Worth Reading Even Today

Though the issues are dated, the characters are not. There are a few clear similarities between the crafty, grasping Harold Transome and certain recent politicians, and not just those from the United States. Modern parallels to the earnest, principled protagonist from the title are, unfortunately, harder to find. Above all, what this book may remind a present-day reader of is that manipulative, bread-and-circuses populism is not the result of universal suffrage – it has always been a staple of real-world politics.

As in several other novels, Eliot uses small-town England as a kind of microcosm in which larger issues affecting the entire nation can play out. She also makes a habit of naming her books after male characters when the protagonist is really a woman, in this case, the admirable Esther Lyon.

Scenes of Clerical Life

Three Bucolic, Charming Tales from Merry Old England

Three Bucolic, Charming Tales from Merry Old England

When this series of stories came out in magazine format, the author was generally assumed by the reading public to be an educated and religious man rather than a somewhat heretical, female autodidact. This demonstrates Eliot’s sensitivity and light touch: though each of these stories touches on issues like religious schism, poverty, and the plight of women, Scenes of Clerical Life didn’t attract nearly the amount of criticism and condemnation Daniel Deronda did.

One of Eliot’s strengths was that she had a keen understanding of her time’s working class, wealthy landowners, as well as the tradesmen, shopkeepers, and clergy who more or less made up the middle class. Though each story involves a different Anglican priest, they’re not necessarily the protagonist. The author seamlessly shifts her focus to portray characters from other walks of life in her signature realistic way.

The Very Thinnest End of the Wedge

Though Eliot herself ended up agnostic, she never became an outspoken critic of religion as such and recognized its social and spiritual value. Although the clergymen in these stories are by no means portrayed as paragons of virtue, and she calls out several areas in which the church could have been doing better, the book’s tone is never strident. Most readers of the time praised Eliot’s realism and recognized that these stories were based on keen observation of real-world events, not made-up plots meant to prove a point.

Scenes of Clerical Life was Eliot’s first published non-fiction work, having been written even before Adam Bede. Her writing style, talent for profound characterization, and skill at gradually building up a story were already firing on all cylinders, though. As always, the length of her sentences and extensive vocabulary would give a present-day creative writing teacher conniptions. That, however, is sometimes the price you have to pay to see the thoughts of a great mind in print.

Final Thoughts

One of the noblest aspects of George Eliot’s best books is her incredible empathy for the people she writes about. None are perfect and some are downright twisted, but each is given their due. Even her villains are often portrayed as victims of their own beliefs and circumstances instead of inherently vicious.

Despite her remarkable sensitivity, Eliot has little mercy for the reader, though. At least in a sense, she intended her work to form a kind of counterweight to the vapid romances the other women of her time read and wrote. Happy endings are never guaranteed with this author, unless you count those of the spiritual, intangible variety.

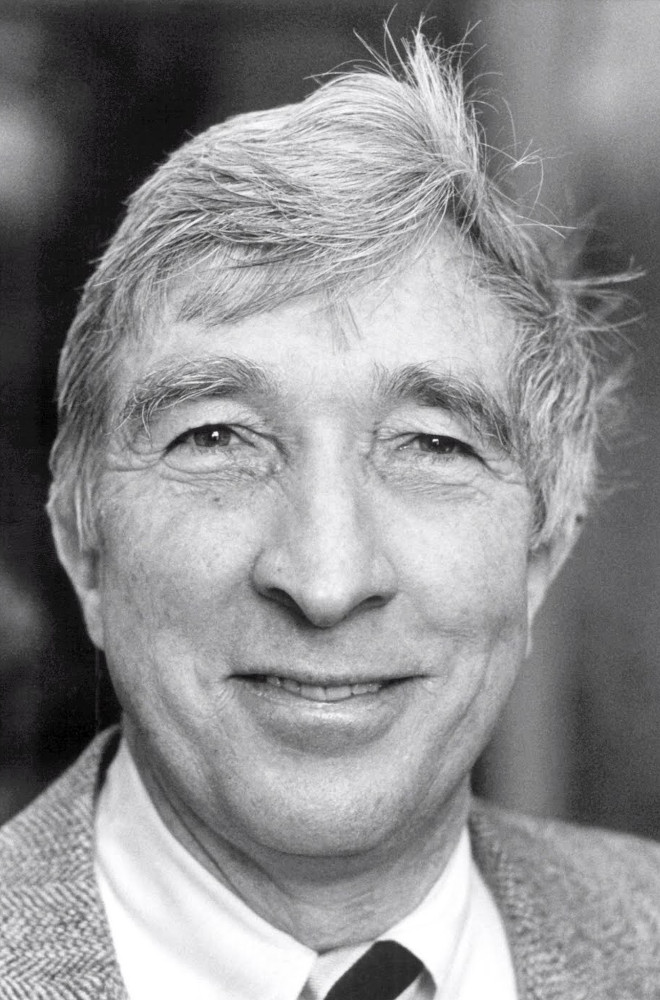

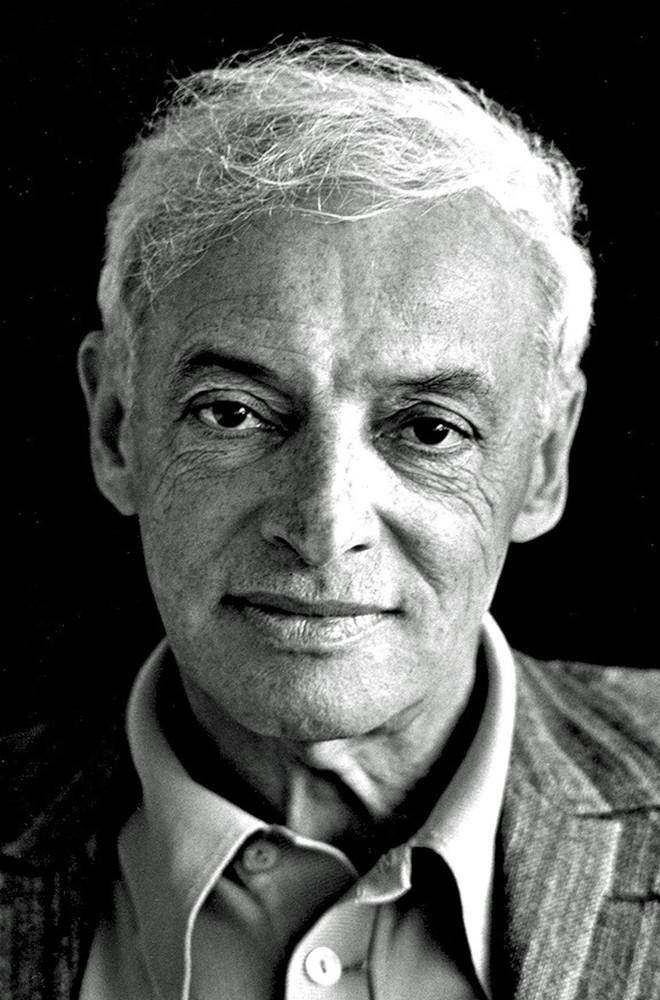

Michael Englert

Michael is a graduate of cultural studies and history. He enjoys a good bottle of wine and (surprise, surprise) reading. As a small-town librarian, he is currently relishing the silence and peaceful atmosphere that is prevailing.